by Lottie Kent

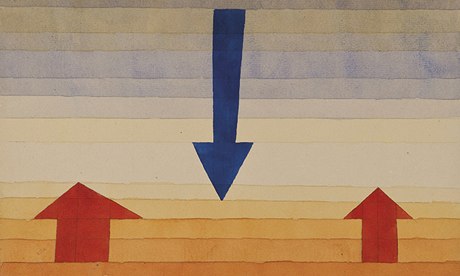

Walk through another doorway and it’s Klee as the outcast under the Nazis’ sudden grip on power and art. On 1 February 1933, two days after the swearing-in of Hitler’s coalition government, the Nazi paper Die Rote Erde carried a full-page article under the headline ‘Art Swamp in Western Germany’. The target was Jewish domination over the Düsseldorf Academy, which had been clinched, so the writer believed, by Klee’s appointment as professor two years before. Even so, Klee had never been more productive than in this tumultuous period. Perhaps his satirical tendencies were driven by the situation; mockery of pomp and power was something he had always represented with a fine subtlety. Indeed, he began to work more closely with stark, hieroglyphic elements, believing language to be intertwined with painting, the rebus twinned with the cipher. Throngs of coded symbols began to take up space in his work from 1938 onwards – circumflexes, cedillas, asterisks, arrows – all speaking of Klee’s growing discontent, in part for the political condition and in part for his onset of Scleroderma, the disease that would kill him in 1940. Certainly, he lost the litheness in his personal outlook, but never so in his art, for whimsy and weakness were always deliberately close in Klee’s work. Colour, though, became perhaps symbolic of his deterioration, and the transition is evident: from light regularly being the main focus, with suns, moons, bulbs and rays pioneering in blank space, the end of his life would mark a shift into richer, angrier colours, with dark backgrounds and black lines moodily overhanging in almost every painting.

Klee understood colour, and he wrote extensively on colour theory. A human fear and tearful bitterness towards dying was chromatically conveyed with infinite power in that final room, and it moved me in a way that only art can. Paul Klee’s was the first artist I could distinctly recognise and I’ve had prints of his work in my house since I can remember. This exhibition at the Tate allows an unparalleled insight into the life and work of an incredible and highly individual artist, unrivalled in variety of style, but ever true to his creative perspective. Put effortlessly into Klee’s own words, ‘art does not reproduce the visible, rather it makes visible’. I would wholly recommend seeing it.

The

Tate Modern’s current EY Exhibition (running until March 9th) is

something of a test. Entitled ‘Paul Klee – Making Visible’, it is a labyrinth

of seventeen (equally ample) rooms. Indeed, I’d hesitate to admit it, but I did

initially think it comprised just the two sweeping halls that were visible when I walked in. Yet, much like

Klee’s work, the floor plan had what is known to anyone well versed in technical

arty-argot as ‘the Tardis quality’. With that said, it isn’t an exhibition

you’d tire of easily: if it weren’t for the inimitability of his visual

idiolect, Klee might as well have been seventeen separate artists, each the

curator for their own room.

It’s

this progression in nuances of style and agenda, then, that allows the viewer

to shift through the gallery arrangement untouched by boredom, slaking their

thirst for artistic evolution with each doorframe. Klee’s own meticulous

cataloguing habits must have been like Ikea instructions for the show’s

organisation - his work is compartmentalised perfectly by periods in his life;

the shifts in artistic approach are mirrors for his changing perception of the

world around him. And indeed, though each artwork is small (as far as the Tate

is concerned), there is space enough around each one for the viewer to engage

with it on specific terms. Perhaps the true Klee anorak would feel that his

individual works are best understood as fragments within the context of his

whole catalogue, but to pore over his oneiric, witty visions of zippy detail as

if masterpieces in their own right is captivation enough for the average

gallery-goer.

At

this point, those who might not be familiar with Paul Klee’s work are probably

lost as to the ‘context’ and ‘visions’ I am speaking of. As many times as he

might be mentioned in the same breath as Matisse, Picasso and his Bauhaus

contemporary Kandinsky, he is just as many times left out. In TJ Clark’s recent

review of the exhibition for London

Review of Books, he referred to Klee as the ‘tragic comedian antidote’ to

his fellow European modernists’ ‘vehemence’ and ‘fundamental coldness.’ But he

was also, somewhat, a product of his time: born in 1879 into an respectable, if

slightly eccentric, family in the then demure Swiss capital, Klee possessed a

fundamental drive to create. It took him a long time, though, to figure out how

to channel himself. His diaries remember the marble table tops of his Uncle’s

restaurant, where he would notice “a maze of petrified layers in which one

could pick out human grotesques and capture them with a pencil.” Indeed, this

small discernment evidences a quality in Klee that can be found still in his

whimsical, translucent layers of watercolours, or expressive and multitudinous

fine lines; the young artist was revealing his heightened sensitivity for sad,

ironic detail in the seemingly mundane.

His

entire survey of work, as it populates the space now in the Tate, can be seen

as an attempt to capture this honest perception. Much of it, especially pieces

produced during his ‘mystical-abstract’ period (1914-1919) seem to hark back to

Germanic fairy-tale visuals: depictions of sleepy hamburgs swept with the

whimsy of Klee’s palette, moonlit Alps, dark geometric landscapes. But his work

resists easy classification, and through his spell at the Bauhaus (1921-1931)

we begin to see Klee the graphic and genius cartoonist, Klee the lover of

architecture and blocky cityscapes, and, after his trip to Egypt in 1928, Klee

the scrupulous pointillist, creating mirages out of the most minute dots.

Walk through another doorway and it’s Klee as the outcast under the Nazis’ sudden grip on power and art. On 1 February 1933, two days after the swearing-in of Hitler’s coalition government, the Nazi paper Die Rote Erde carried a full-page article under the headline ‘Art Swamp in Western Germany’. The target was Jewish domination over the Düsseldorf Academy, which had been clinched, so the writer believed, by Klee’s appointment as professor two years before. Even so, Klee had never been more productive than in this tumultuous period. Perhaps his satirical tendencies were driven by the situation; mockery of pomp and power was something he had always represented with a fine subtlety. Indeed, he began to work more closely with stark, hieroglyphic elements, believing language to be intertwined with painting, the rebus twinned with the cipher. Throngs of coded symbols began to take up space in his work from 1938 onwards – circumflexes, cedillas, asterisks, arrows – all speaking of Klee’s growing discontent, in part for the political condition and in part for his onset of Scleroderma, the disease that would kill him in 1940. Certainly, he lost the litheness in his personal outlook, but never so in his art, for whimsy and weakness were always deliberately close in Klee’s work. Colour, though, became perhaps symbolic of his deterioration, and the transition is evident: from light regularly being the main focus, with suns, moons, bulbs and rays pioneering in blank space, the end of his life would mark a shift into richer, angrier colours, with dark backgrounds and black lines moodily overhanging in almost every painting.

Klee understood colour, and he wrote extensively on colour theory. A human fear and tearful bitterness towards dying was chromatically conveyed with infinite power in that final room, and it moved me in a way that only art can. Paul Klee’s was the first artist I could distinctly recognise and I’ve had prints of his work in my house since I can remember. This exhibition at the Tate allows an unparalleled insight into the life and work of an incredible and highly individual artist, unrivalled in variety of style, but ever true to his creative perspective. Put effortlessly into Klee’s own words, ‘art does not reproduce the visible, rather it makes visible’. I would wholly recommend seeing it.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.