by Sam Kent

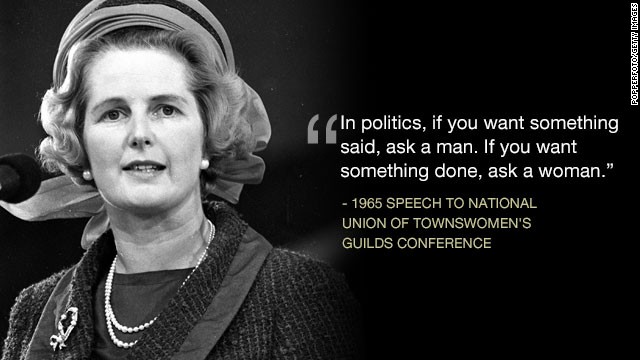

Margaret Thatcher was, in a sentence, a divisive yet

historical political figure. However, regardless of political opinion, her

motivation and urge to be proactive cannot be denied, and even the most

partisan of Labour supporters could harbour some measure of admiration for her

in that regard. Despite this, she is not, at least not in mainstream political

culture, seen as a significant feminist icon or role model – and in that sense she is unfairly interpreted in modern society.

This fact was brought to my attention by the attitudes towards Hillary Clinton as a feminist pioneer and a figurehead of cultural progression as she surges towards victory in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination. With the Republican Party seemingly in turmoil and without a candidate with genuine general appeal, it seems as though she will be the one to break America’s run of 44 consecutive male Presidents (counting Grover Cleveland as both the 22nd and the 24th US President). In this regard, Thatcher is entitled to a great deal of praise, as she was the first female British Prime Minister and the only one to this day. Yet Clinton is receiving significant acclaim for her contribution to the gender equality movement in general, without yet having even been nominated as the official Democratic candidate for this November’s Presidential Election.

This fact was brought to my attention by the attitudes towards Hillary Clinton as a feminist pioneer and a figurehead of cultural progression as she surges towards victory in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination. With the Republican Party seemingly in turmoil and without a candidate with genuine general appeal, it seems as though she will be the one to break America’s run of 44 consecutive male Presidents (counting Grover Cleveland as both the 22nd and the 24th US President). In this regard, Thatcher is entitled to a great deal of praise, as she was the first female British Prime Minister and the only one to this day. Yet Clinton is receiving significant acclaim for her contribution to the gender equality movement in general, without yet having even been nominated as the official Democratic candidate for this November’s Presidential Election.

However, it should be stated that

the success of one woman does not equate to progress for women in general. In

11 years as Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher promoted only one other woman to Cabinet. As

well as this, she had little time for policies regarding childcare provision,

and overall never associated personally with the feminist movement.

Nevertheless, just because she did not consider herself a feminist, does not

mean that other people cannot idolise her as one. She has, no-doubt, inspired

many women with a profound interest in politics to follow their dreams, and has

been a figure towards whom those concerned can look, and see that success is

possible; even more encouragement can be found in the fact that she succeeded

in rising up through the ranks of the notoriously-backward Conservative Party,

realising her aims in a decade in which women’s rights and opinions were

regarded with shameless insignificance within society.

The percentage of women in the House of Commons nowadays is still unrepresentative of Britain’s gender demographic as a whole (29% in the Commons to roughly 50% nationwide), but it is entirely feasible that this number would be lower had Thatcher not provided an example of a woman being able to get into House of Commons, have her voice be heard, and push aside those who would tell her that these achievements were not possible.

The percentage of women in the House of Commons nowadays is still unrepresentative of Britain’s gender demographic as a whole (29% in the Commons to roughly 50% nationwide), but it is entirely feasible that this number would be lower had Thatcher not provided an example of a woman being able to get into House of Commons, have her voice be heard, and push aside those who would tell her that these achievements were not possible.

In conclusion, The Iron

Lady’s rejection of feminism during her time at the helm of British

politics means that we cannot respectfully call her a feminist, as giving

someone a title or name, regardless of how positive and progressive it may be,

is unfair if the person in question does not associate with it themselves.

However, the opportunities and potential that she has helped other women

realise, as a result of her legacy and achievements if not her style of

leadership and personal beliefs, have irrefutable tones of feminism and have helped push

gender equality that modern feminists, female and male alike, aspire to

achieve.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.